Filestash plugin development

General Idea for Plugin

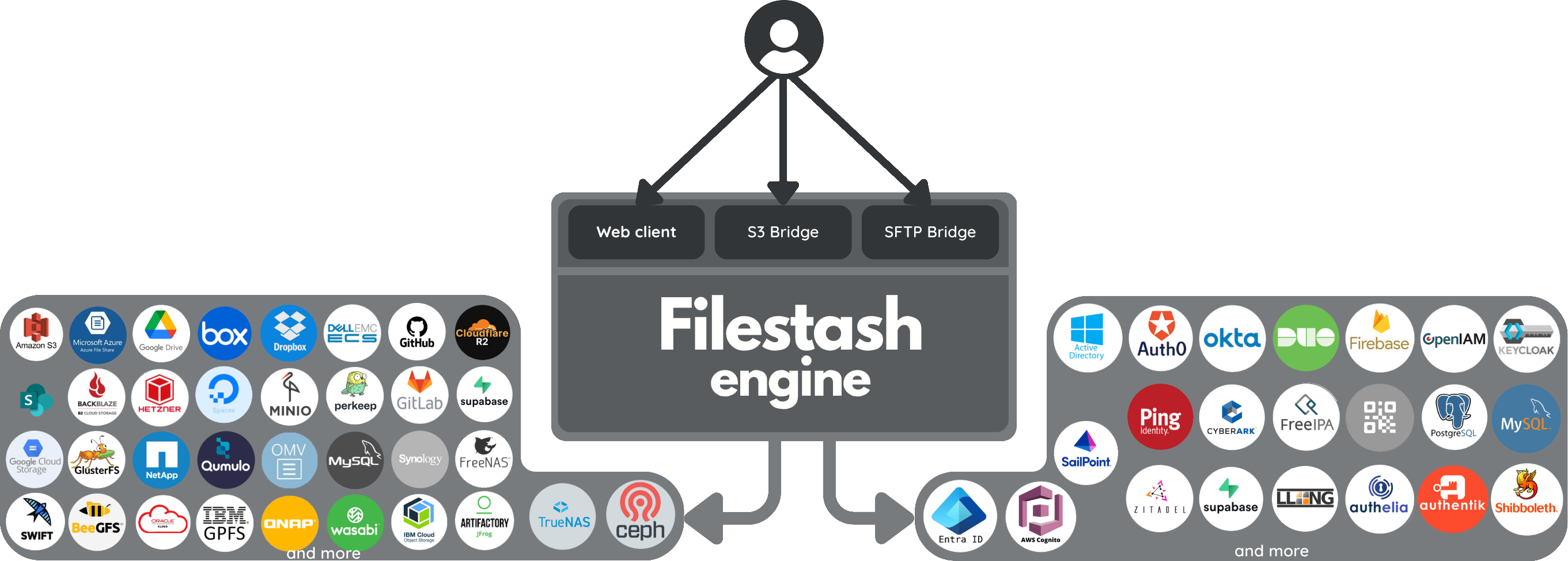

You may have seen this diagram before:

If you wonder how is this possible to provide support for all those systems, the answer is one word: “polymorphism”. All the bubbles on the left side represent storage plugins. Each one is an implementation of the IBackend interface. The bubbles on the right represent plugins that implement another interface (called IAuthentication). Filestash itself is simply the engine that runs everything and connects all the pieces together.

The actual scope of plugins is much wider than what this diagram suggests. This page is intended as a reference for plugin developers who want to customise or extend Filestash. Once you look under the hood, you will find that Filestash provides two very different kinds of plugins:

-

Compiled Plugins: built directly into the server binary. These have existed since the early days of Filestash and have access to the entire surface area for customisation. Those are the most powerfull but changing anything requires to recompile the software.

-

Runtime Plugins : easier to use since they do not need to be compiled into the software. These are ZIP files placed in the plugins/ directory. As of today, their scope is limited to frontend customisation, but work is ongoing to extend them into the backend as well via RPC

This guide explains how both kind of plugins work, what they can do, and how to create your own extensions for Filestash.

Plugin Discovery

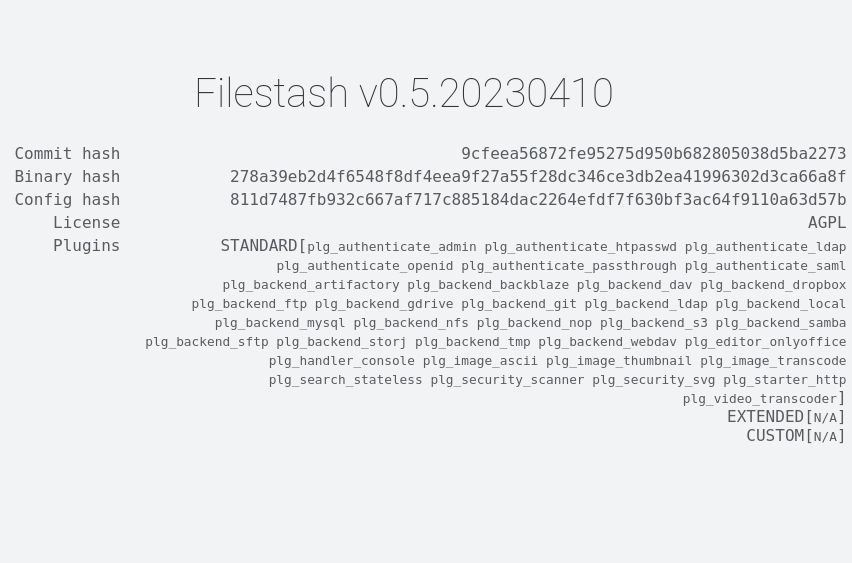

How do you know which plugins are active in your Filestash instance? You can check this from the /about page:

To add, remove, or change the plugins you are using, the procedure depends on the plugin type:

-

Compiled Plugins: update the list of plugins in

server/plugin/index.goand recompile Filestash. The resulting binary will include only the plugins you selected. -

Runtime Plugins : place or remove ZIP files in the plugins/ directory. These are loaded at startup. During the boot process, Filestash inspects the manifest.json inside each plugin and registers the modules it finds.

Compiled Plugin

Compiled plugins are written in Go and must be built directly into the Filestash binary [*]. We have developed many of them, which you can browse on the plugin documentation page. If you want a starting point for exploring the code, you can look through some examples in the repository.

There are essentially two kinds of compiled plugins:

- Plugins that implement an interface to customise or extend a part of Filestash. These hook into the core engine through one of the available interfaces and handling one particular aspect of Filestash which are all details in the available interfaces section

- Plugins that could live as standalone services, but are shipped alongside Filestash for convenience. A good example is

plg_gateway_sftp, which exposes your Filestash instance as its own SFTP server. It may as well live in a separate process as it only rely on the public API

[*]: There is one special case exception. The plg_dlopen plugin can load .so files dynamically to provide a form of runtime extension. This approach is not beginner friendly and requires compiling and deploying the core binary and all plugins together as a single unit. It is expected to be deprecated once runtime plugins gain support for backend functionalities.

Structure of a Compiled Plugin

The scaffold for a compiled plugin always follows the same pattern. You register your implementation of a core interface using Hooks.Register:

package plg_interface_example

import (

. "github.com/mickael-kerjean/filestash/server/common"

)

func init() {

Hooks.Register.XXX(Impl{})

}

type Impl struct {}

func (this Impl) ...

If you prefer to start from a minimal working example, there are documented sample plugins you can copy from. Two good ones are: plg_search_example and plg_authorisation_example

Available Interfaces

Compiled plugins hook into the Filestash engine by implementing one or more interfaces. The full list of hooks is documented here. Below is a practical overview of what you can find in there:

-

Hooks.Register.HttpEndpoint: Create your own HTTP endpoint. This can be used to expose an API, serve static files, or create some pages. A good open source example is plg_handler_site, which exposes shared links as websites, in a similar fashion to SFTP + Apache or S3 static website hosting.

-

Hooks.Register.AuthenticationMiddleware: Controls how a user logs in: SAML, OIDC, LDAP, passthrough, SQL, QR code, and more. A simple example to study is plg_authenticate_admin. The Setup method is to define the configuration fields visible from the admin console, Entrypoint is to display some sort of login page and the callback is the last step of the authentication which will emit the user attributes if user successfully authenticate

-

Hooks.Register.AuthorisationMiddleware: Controls what a user can do and where. Authentication answers “who are you?”, authorisation answers “what are you allowed to touch?” This is the basis from which we have implemented a range of authorisation options to configure authorisation in Filestash, all of those are implementations of this interface.

-

Hooks.Register.SearchEngine: Lets you redefine how search works. The default is a simple recursive search (

plg_search_stateless), but there are many variants documented, for example using the full text search plugin in S3 might not be a great idea if you have a very large bucket to index because of bandwidth cost, etc… -

Hooks.Register.CSS: Inject static CSS into the final binary. Perfect for baked in themes.

-

Hooks.Register.CSSFunc: Same as above, but the CSS is generated dynamically at runtime.

-

Hooks.Register.Onload: Execute code after Filestash has finished initialising itself. This is a convenient place to: Load or register configuration options, Initialise connections (for example to a database), Perform any other one-time startup logic

-

Hooks.Register.Middleware: Wrap HTTP handlers with additional logic. Typical uses include adding captchas in

plg_security_captcha, antivirus checks inplg_middleware_antivirus, quotas handling inplg_middleware_quota, idle session cleanup inplg_middleware_iddlesessionand the monitoring of active transfer and connections inplg_middleware_transfer -

Hooks.Register.StaticPatch: Patch any files in the frontend application. This hook is what is beeing called by the “patch” runtime plugin, making it possible to inject a diff that will change the frontend code. A good example can be found here

-

Hooks.Register.WorkflowTrigger and Hooks.Register.WorkflowAction: These two interfaces are used by the workflow engine. A workflow is made of: a trigger, which starts the workflow run, and one or more actions, which are the steps executed as part of that run. You can find examples of triggers in here and actions in here

-

Config Generator: By default, configuration is stored in config.json, but this is just a reasonable default. As hinted in this file, you can override LoadConfig and SaveConfig via a Go generator to use your own Configuration Repository. This is exactly how those plugins work.

-

Hooks.Register.Starter: Defines how Filestash boots. From a simple HTTP server on port 8334 using the default

plg_starter_httpto a Tor onion service, HTTPS setups withplg_starter_httpsfsor via LetsEncrypt usingplg_starter_web, if you have compliance requirements that enforce only some particular ciphers, Starter plugin is how to get it done. For the full list of Starter plugin we have available: check this out

We have already covered the most used plugins but there are some other niche one like:

-

Hooks.Register.Thumbnailer: To generate thumbnails for a particular mime type. By default

plg_image_chandles this through hand-tuned C code, but you can plug your own likeplg_video_thumbnailto generate thumbnails for video via ffmpeg. The full list of thumbnailer is available here -

Hooks.Register.Favicon: Replaces the default favicon with your brand’s one. Mostly useful for baked-in white-labelling.

-

Hooks.Register.ProcessFileContentBeforeSend: Intercepts file content before it is sent to the client. Great for: watermarking, transcoding, antivirus, steganography, content filtering, and other “last mile” processing. A fun example with

plg_image_asciithat converts images into ASCII art. -

Hooks.Register.AuditEngine: Produce audit trails for compliance heavy environments (AFNOR NF Z42-013) or just have everything connected to your existing SIEM

-

Hooks.Register.Metadata: Attach, read, or enrich metadata from any source (S3 tags, archivist systems, BagIt, Perkeep, etc.). The default implementation relies on sqlite

-

Hooks.Register.Static: Only kept for backwards compatibility. Do not use it for new work.

-

Hooks.Register.FrontendOverrides: Old mechanism predating the current frontend architecture

-

Hooks.Register.XDGOpen: The original way to create frontend apps inside Filestash. Left for historical reasons. Example reference with

plg_editor_onlyoffice

Runtime plugins

Structure of a Runtime Plugin

Runtime plugins are packaged as ZIP files and placed inside the plugins/ directory. Each plugin must contain a manifest.json file, which declares the modules that make up your plugin. A typical manifest looks like this:

{

"author": "Filestash Pty Ltd",

"version": "v0.0",

"modules": [

{

"type": "css",

"entrypoint": "index.css"

},

{

"type": "patch",

"entrypoint": "index.diff"

},

{

"type": "favicon",

"entrypoint": "favicon.png"

}

]

}

The modules array defines the functionalities your plugin provides. Each entry must include:

type: the module type (eg:css,patch,favicon,xdg-open)entrypoint: the path to the file implementing that module, which must exist inside the ZIP archive

Filestash reads the manifest at startup and automatically loads the modules your plugin declares.

Common Error : Do not unzip anything inside the plugins/ directory. Keep the ZIP file in its original form as a .zip file, Filestash loads modules directly from the archive.

Available Interfaces

Runtime plugins currently focus on frontend customisation. Over time, their capabilities will expand to match what compiled plugins can do, but as of today the following module types are supported:

- css: inject custom CSS into Filestash to adjust styling or apply a full theme. For inspiration, see the theme examples from the documentation, each of which includes a css module in its manifest. as the name implies, this is to add your CSS to Filestash to customise the design. If you want some inspiration, go check the theme section of the documentation, they all contains a css entry in their manifest.

- favicon: replace the default Filestash favicon with your own, useful for branding or white-label deployments.

- xdg-open: register a custom application handler for one or more file types. This is the mechanism used to build viewers/editors directly inside Filestash. See the section xdg-open plugins in depth

- patch: the go to module whenever your plugin involves adding / removing / changing some javascript. Do you want to change the frontend in some ways? Patch plugin is the go to tool for this. See the details in the patch plugins in depth section

xdg-open plugins in depth

xdg-open plugins is to open specific file types using your own viewer / application. There are many examples of these plugins in the repository. A typical manifest looks like this:

{

"author": "Filestash Pty Ltd",

"version": "v0.0",

"modules": [

{

"type": "xdg-open",

"entrypoint": "/loader_swf.js",

"mime": "application/x-shockwave-flash",

"application": "skeleton"

},

{

"type": "xdg-open",

"entrypoint": "/loader_psd.js",

"mime": "image/vnd.adobe.photoshop",

"application": "image"

},

...

Each xdg-open module includes the standard type and entrypoint fields used by all runtime plugin types, plus two additional fields:

mime: which mime type this loader handlesapplication: which Filestash application shell should host the viewer

In the example above:

-

flash / swf files are handled by loader_swf.js using the skeleton application. Using

skeletonmeans you start from a blank canvas. Filestash only expects your loader to export a default function from which you build the entire UI yourself -

psd files are handled by loader_psd.js using the built-in image application. Using

imagegives you a full image viewer UX for free with zoom handling with mouse or pinch, keyboard navigation, layout and more. Your loader only needs to implement the IImage interface and convert the PSD into something the browser can render natively

Except skeleton, the other application shells define small interfaces you can implement to generate pre made viewer apps that you can then customise. Filestash provides several shells depending on the content you want to support:

-

table: for tabular formats. You can see it in action with: parquet viewer, and sqlite viewer (which even lets you query the db). The interface to implement is available here -

map: for geographic formats. Example: the shp viewer and the interface to implement -

3d: for Three.js based 3d viewers. Example: this package adds support for many 3d formats. The interface to implement is available here -

image: for image based formats. Example: the psd viewer. The interface to implement is available here -

skeleton: for building your own viewer from scratch. Example: this docx viewer

Patch plugins in depth

Patch plugins are your go-to method for updating JavaScript so the software looks and behaves exactly the way your use case requires. With a patch plugin, you ship a git style diff of the frontend code; Filestash will execute your patch dynamically so your changes get reflected in the js code. Because patches operate on the full frontend assets, the surface area is effectively 100% of the frontend code, you can change anything. The possibilities are limited only by your own creativity.

A couple real exampless of what you can do with them:

-

Customising iconography and branding: One of the most common uses internally is to add banners, swapping out icons to match a design system and add buttons for various things in various places. For a concrete example check out this theme

-

Handling cold storage tiers like S3 Glacier: When data is in Glacier, it can’t be read directly but needs to be recalled, which can take anywhere from a minute to a few hours depending on the phase of the moon. With a patch plugin, we added a “Recall” button directly in the UI so Glacier files can be pulled back on demand.

Note on patch plugins: Patch plugins were one of the primary expected benefits after the completion of the 2025 frontend rewrite, when we moved from React to vanilla JS. Under React, supporting frontend plugins would have required exposing a huge number of extension hooks. But no matter how many hooks you expose, you never reach 100% coverage, someone will always need something impossible within the constraints of the API. That’s exactly what happened with Cursor: it could have been “just” a VS Code plugin if the VS Code plugin surface area had been sufficient, but it wasn’t, which forced them to fork the entire editor. Meanwhile, every extra hook adds overhead for everyone, and this become a 1% of users needing something kind of problem that lead straight onto the classic JIRA problem. So instead of inflating the plugin API, we support git-style patches on the frontend. In a non-Lisp world, this is the only realistic way to give plugin authors complete freedom without turning the core product into an unmaintainable heap. Patch plugins are the embodiment of that philosophy: total flexibility, zero bloat.

Managing Plugin Configuration

By default, Filestash stores its entire configuration in a single file: config.json. The admin console is essentially a friendly UI wrapper around this file. It reads and writes configuration entries so administrators don’t have to manually edit such JSON directly.

Plugins are allowed to extend this configuration. This allows you to expose settings in the admin console so users can enable, disable, or customise the behaviour of your plugin. A simple example of this pattern can be seen in plg_handler_site, which defines configuration fields controlling whether shared links should be exposed as static websites with various options to enable autoindex and cors.

When a plugin needs configuration, the standard approach is to create a config.go file inside your plugin package and register configuration fields during the Onload phase. The structure typically looks like this:

package plg_xxx_xxx

import (

. "github.com/mickael-kerjean/filestash/server/common"

)

func init() {

Hooks.Register.Onload(func() {

PluginEnable()

// ... add more config options

})

}

var PluginEnable = func() bool {

return Config.Get("features.foobar.enable").Schema(func(f *FormElement) *FormElement {

if f == nil {

f = &FormElement{}

}

f.Name = "enable"

f.Type = "enable"

f.Target = []string{}

f.Description = "Enable/Disable the foobar feature"

f.Default = false

return f

}).Bool()

}

// ... add more config options

This pattern ensures your configuration fields are registered early during startup, appear automatically in the admin console, and are cleanly accessible from your plugin code.